Bathory – “Twilight of the Gods”

December 1st, 2017

I am not saying anything revolutionary when I call “Twilight of the Gods” a masterpiece. Within the metal community the album is regarded as a classic, though, oddly enough, it does not seem to hold quite the same status in the broader music world, even when compared with other black/viking/folk* metal classics. Most of the people reading this are probably wondering why I would even bother to write something like this given that everyone who has even a mild interest in metal will encounter this album on nearly every best of list that covers a remotely relevant subgenre. The reason I think such an endeavor is worthwhile is due to an odd paradox I have noted when it comes to metal. Far more than any other scene I am familiar with, the metal community holds its classics in total veneration. People will go to great lengths to present detailed overviews and write ups to subgenres, and compared to most subgenres, there is a far greater emphasis on history in the metal world. However, while the amount of overview oriented material available about metal is truly phenomenal, there is comparatively little in the way of detailed analysis of specific works.

For some odd reason, even though the metal community absolutely adores its great treasures, there is not a lot of super in-depth discussion concerning them. Thus I do think that it is worth the time it took to prepare something of this size for an album that just about every metalhead knows by heart. My goal is not to turn new people on to the recording (though it would be great if I could do that) but to increase the appreciation of people who are already familiar with it.

I can think of no better album to provide such an assessment of than Bathory’s “Twilight of the Gods”. Quorthon’s early album’s are some of the most influential metal recordings ever made, but rather than appeasing the momentary whims of fans by sticking to the exact same thing that worked for him in the past, trying to force his sound into more commercial territory, or introducing some senseless gimmick to maintain his relevance, he created an album that takes all of the things he learned over his years as a trailblazer and solidifies them into a unique vision that sounds like nothing that has been made before or since, despite the best efforts of thousands of imitators.

There is a seamless blending of a vast variety of different music, from the expected subgenres like doom and traditional metal, to the folk music of his native land. No one element is ever thrust to the forefront, but rather, like the work of earlier rock musicians such as Bruce Springsteen, he uses each instrument to contribute to the whole without forcing our attention any of their singular achievements. In doing so he creates a more spacious style of music that never sacrifices the aggressive power of his chosen genre, and at the same time never finds itself cluttered with too much going on at once.

In the art world, the term Old Master exists for those skilled painters who, quoth the wiki, were “fully trained, …Masters of their local artists' guild, and worked independently”, in the years preceding the eighteenth century. While metal does not have enough of history behind it for this criterion to be applied literally, in the years since the term was created, our attention spans have shortened enough that two and a half decades of 21st century time roughly equal the same amount of centuries in an earlier age. Because of this, I believe “Twilight of the Gods” can be called the crowning achievement of an Old Master. Quorthon had reached the point in his career that his expertise in the music he was making was unequaled. He was regarded as the most significant influence by the bands of his native land that followed in his footsteps. Don’t believe me, check out Fenriz’ “Black Metal University” video or nearly any interview with an early Norwegian black metal musician (for some reason interviewers are drawn to questions about influences like pedophiles are to Disney World). Finally, his work was always completely his. While he borrowed elements from some of the nearby extreme metal scenes that fit what he was going for, they were always filtered through his unique vision for what he wanted to accomplish with his music. “Twilight of the Gods” represents the apex of all three criteria.

With that out of the way I will start things off by giving a little overview of each of the dominant instruments, which are of course the big four instruments of rock music: the voice, guitar, bass, and drums, in addition to the lead vocals, backing vocals, and lyrics. After that I will delve deeper into the individual songs before bringing things to a close.

In Quorthon's vocal work we can see a progression away from the conventional singing styles of both rock and metal in his early albums as he searched for a way to make his voice fit in with the sounds he was producing. In doing so he, along with his fellow usual suspects of early extreme pioneering Venom, Celtic Frost, Slayer, Bulldozer, and Sodom pioneered the way metal vocals are done to this day. More than most scenes, the metal community is perfectly happy to let a band rest on the laurels of early achievements, provided they hit anywhere near as high as Bathory's first three albums. Quorthon could have easily hit the turn of the decade putting out releases that aped the formula he brought to perfection in "Under the Sign of the Black Mark", while focusing on playing all his classic hits on the festival circuit every summer. I don't think I am straying into the unimaginable by suggesting that he would have made much more money if he followed that route. However he chose not to do so. As things have turned out Bathory is an embodiment of upper-echelon metal in terms of both the respect accorded to him and his actual talent, but plenty of bands have moved further and further into experimentation and found that they left their fan base behind. It's easy to forget now that his viking metal work has entered the canon but these albums really do fit the term avant-garde, not in the sense of a bunch of French people slicing their eyeballs apart and calling up ants from their hands, but in the original sense of an advance force of an army that goes ahead of the general body of the troops to perform (typically more dangerous) tasks necessary to allow the main forces clear passage.

Quorthon’s singing fits perfectly with the overall sound he was going for. Above all, I think the most basic goal for “Twilight of the Gods” was to take Norse mythology, and, either extracting key concepts that fit well with the heavy metal aesthetic or drawing from the ideological values presented in these myths, write original material that presents similar ideals. From there it was a matter of developing a synthesis of a number of different metal subgenres so that the various themes that the songs evoke, most notably a sense of epic scope, aggressive violence, and melancholy, are all augmented.

To that end Quorthon develops a singing style that suggests the grand strife of the titular conflict without resorting to the near-comic baroque of many Power Metal bands. He knew the limitations of his voice, and knew that he would not be competing with Rob Halford or Michael Kiske in the battle of the frequency ranges, but rather than attempting to do a half-assed imitation of Hansi Kürsch or retreating back to the harsh singing he knew he could do well, Quorthon decided to turn his limitation into an advantage. The thing about traditional folk music (regardless of its origin) is that it is by definition the music of the people, so it was sung by farmers in the field and tailors trying to relax in the tavern rather than professional singers who had the free time to fully dedicate themselves to perfecting their voice. This is exactly what Quorthon sounds like: the best singer in the village who is always called to perform during festivals, not the castrated eunuch who spends his days in the palace or cathedral treating the nobility to his glorious falsetto.

Quorthon’s voice is decidedly human, which fits perfectly with his turn towards a mythic tradition sung out by either warriors around a campfire or else skalds who, while possessing an impressive technical knowledge and memory, were not the product of the kind of formal training that later European singers would undergo. Some clever soul may be inclined to point out the contradiction in my assertion that a mythic tradition featuring giants, oversized wolves, serpents, and incredibly powerful Gods being somehow more human than later European traditions. I, however, like Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell, believe that the myth is a culture’s means of reaching into their collective psyche and expressing universal truths that go beyond the limits of traditional expression, yet shine in the hearts of every human being. Hence, to me at least, the visible imperfections of Quorthon’s voice do not clash with his subject matter but rather enhance it.

This humanity really shines in one of my absolute favorite elements in this album, the passion-wrought, voice cracking wails that Quorthon judiciously employs at key moments. I will be delving into greater detail regarding these beautiful lunges when I get into the song by song assessment, but for now I will simply say that they are a perfect means of combining the intensity of the high pitched wails seen in countless metal bands with the folk traditions he sought to emulate. Rather than flawlessly stretching his voice to the targeted pitch, Quorthon lets his throat undergo the natural scratches and distortions that occur when a normal human attempts to go that high, and then uses them as means of enhancing the raw intensity of the lines he wishes to draw particular attention to.

The backing vocals of “Twilight of the Gods” are an equally exceptional achievement. They at once evoke the ancient past and come off as entirely innovative. They contrast the heavier elements of the music while at the same time enhancing rather than diluting them. The melodic quality of these chants strikes the listener without standing out against the broader sound, unlike many other bands who try to incorporate "poppy" hooks into heavy music. They dig into your skull while at the same time succeed in evoking the same ideas the rest of the music is aiming at. They are variously employed as a chorus, a means of enhancing the lead vocals of a verse, or as a transitional device. All of these applications are magnificent in their own right and show off unique facets of not just Quorthon's songwriting chops, but, given that he multitracked all of the component vocals himself, his gift for singlehandedly crafting nuanced harmony, an incredibly difficult task when you don’t have a group of vocalists to work with and must rely on doing each voice one by one.

I don’t know what the music historians have to say about how the Norse sang in their pagan heyday, but I know that it isn’t much. Given that we have no idea what the music of Greece or Rome sound like (save Seikilos' Epitaph) and both of those cultures have stood taller in the western mind than the Scandinavians, there really isn’t much hope for accurately reproducing the works of a largely illiterate warrior culture. I don't know where my idea of what Norse music should sound like came from, likely a complex web of cultural influences, most notably metal bands and fantasy films, which are then weighed subconsciously by some unacknowledged set of criteria according to my trust in the source. However, based on this half-baked understanding, coupled with a little bit of knowledge in their poetic tradition, of which a large portion was either sung or chanted, and gut instinct, I have no difficultly believing that I would hear singing similar to these backing vocals if I found myself in any of the old halls. The approach used by Quorthon in arranging the backing vox would lend itself quite nicely to use as a refrain when the poet had finished singing a line. Think of the way a Chinese Guqin (table harp) is used after a line or verse of poetry, or the way African music uses call and response. An added benefit of this is that, given the social environment of the halls (where the sagas and poems were recited), it would provide a means of allowing the entire group to join in with the telling of the story.

Obviously this is all baseless speculation. The point is, unlike many viking metal bands, who take an instrument that (at best) could be plausibly dated to pagan times, and then use it to produce hooks and riffs derived from the western tradition (which even in its earliest medieval precursors postdates all but the last holdouts of Norse paganism), you can see that Quorthon put some thought into how he was going to connect his music with the traditions of his ancestors.

In terms of specifics, the backing vocals tend to be of two varieties, either wordless singing, which is almost always either straight vowel sounds, or vowel sounds fronted by a “w”, or else actual lyrics. There is a great deal of differentiation between when the two are used, and while it varies from song to song, the general pattern is that the vowel sounds are used as a way of augmenting a key sections of the song (often behind Quorthon’s lyrics) while the spoken lines are designed to draw attention to themselves.

Quorthon, perhaps more than anyone from the first wave of black metal, was responsible for taking the gritty, glorious filth of Venom and infusing it with a more competent, but equally harsh, level of technical proficiency. I think the biggest single innovation of early Bathory is the way Quorthon built up many of his riffs out of a handful of chromatic notes played mostly on the beats in a reasonably steady manner using super fast (especially for the time) tremolo picking. To illustrate what I mean, compare the riffs used in Slayer’s “Black Magic”, off 1983’s “Show No Mercy”, a fairly representative example on the heavy end of the early thrash movement, to the two main riffs used in Bathory’s “Possessed”, off “The Return”, from 1985. Both use tremolos, both have long stretches where either a single note (in Slayer’s case) or a two note pseudo-power chord (in Bathory’s) are held, and both use very dissonant melodies. However, the riff in “Black Magic”, has a much greater degree of rhythmic variety to it, having the fast parts on the open string transition into sudden halts when the notes are struck. Quorthon, by contrast, plays at the exact same rate from the start of the riff to the finish. The points where he transitions from one note to another are more regular too. On “Black Magic”, Slayer use an additive 4+5/4 meter (i.e. one bar of 4/4 followed by one bar of 5/4) that provides a sense of variety, where on the first part alternates between a beat of tremolo picking and a beat of the melody, and on the second part there is one beat of tremolo and four beats of a melody. Instead of something like this, Quorthon keeps the changes in his tremolo constant and plays exclusively in 4/4. The first riff repeats the same pattern twice over in each bar, while the second has a two bar pattern that has three beats of slower playing and five of tremolo picking.

This style of guitar playing turned the music from having a riff-centric focus to drawing the attention of a listener to a steady atmospheric drone that digs into the recesses of your mind. It would go on to define the early 90s black metal movement. While it is neither exclusive to black metal nor a requirement of the subgenre, if I had to guess, the kind of guitar playing Quorthon started developing on his s/t and “The Return”, and perfected on “Under the Sign of the Black Mark”, is the first thing that would signal to a listener that what they are listening to is in fact black metal. While there are plenty of black metal songs that do not use this technique, I can think of a few full albums that avoid it.

Now as I said before, to simply have a credit of that magnitude on ones resume would be enough for most acts to either spend the rest of their career retreading the same territory or else, their scene cred firmly established, they might move on to a more mainstream career. Quorthon does neither of these things. Instead he decides to take everything he has accomplished and totally overhaul his playing, creating a style that at once looks back to the guitar playing of early metal and looks foreword to what future viking metal bands would be doing. To give an example of this, lets look at a few examples of the variety of techniques employed on the title track. We can see examples of:

-A dreamy opening sequence that induces a sense of misty calm which he promptly obliterates once the electric guitars enter.

-An acoustic guitar that plays standard chord sequence, nice consonant little fills separating different [line pairs] of the verse, and gorgeous folk-influenced fingerpicking patterns.

-A ton of hard, steady electric guitar chord sequences that range from simply defining the chord at the start of the bar to rhythmically intricate riffs.

-Riffs that alternate from the aforementioned chord sequences to single note melodic lines.

-Chugging, on the beat, A, B, B, B, style riffs a la more traditional metal.

-Some of the most beautiful solos in not just viking metal, or even metal of any genre, but all rock music.

All of this is fused together to create a unified style that remains consistent enough throughout the album to give it a sense of wholeness, while incorporating enough variety to keep the listener’s attention. You don’t ever see anything quite as aggressive as his earlier playing, but at the same time it is clear that the guitar work is built from what he learned writing his earlier albums, in addition to the sum total achievements of metal guitar playing up to that point.

The guitar solos on this album are not haphazard sluices of notes or stiff scale exercises, nor is there even a trace of incompetence in them. I'm not going to say the solos here are among either the most complex or the most technically demanding, if that is your sole benchmark for a great guitarist then there is plenty of tech death and prog that outshines him, but what I will say is that they possess a kind of natural fluidity that I think is gorgeous. It is the kind of playing that would lead a guitarist of vastly inferior skill to think that they had a shot of playing them with when in fact they are in fact miles out of his league (speaking purely theoretically of course). I am with the Daoists in believing that a guitar solo, as a general rule, sounds best when it doesn't drag every spotlight into the room onto itself. This does not mean a solo should be a background element, there is a reason they call it a solo, but when you listen to a guitarist who is more committed to the broader vision of the music than to his ego, the end result is almost always a sound that seems to flow naturally from the music itself rather than one that constantly tries to push itself above the flow in order to stand out. Technical proficiency should be a tool rather than the default mode of operating. When a skilled guitarist suddenly lets loose a burst of incredibly proficient playing that draws ones attention it is a thing of beauty (see the end of Under the Runes), but when the solo from start to finish is just a nonstop display of virtuosity that same skill becomes boring. When a sailor tries to force his boat to move against the wind the end result is that he gets nowhere, but when he uses the very force of the wind to skillfully tack, he can move in any direction regardless of where the wind is coming from. I am not suggesting that Quorthon has read a word of Laozi or Zhuangzi (I obviously have know way of knowing that), but he understands the Dao intuitively, which is the only true way to understand it (the Dao that can be spoken is, after all, not the eternal Dao).

Quorthon’s solos often implement the main melodic lines of the song, but he does not go the route of "Smells Like Teen Spirit" by simply imitating them, but rather uses the instrument and form to expand on the melodic sense of the vocals, adding notes and bends to give it the effect of an enrichment rather than an imitation. There is an ebb and flow in intensity that gives one the impression that they are observing a living thing, with the grand crescendos not being firmly tied to the underlying rhythm, but acting in accord with it the way waves rise and fall yet also act withing the framework of the shifting tides. Each time the underlying melody hits a significant chord, the solo connects with it. While it varies whether this is done with consonance or dissonance, the one constant element is the careful attention paid to how the melody relates and interacts with the harmony.

One of less discussed achievements of “Twilight of the Gods” is the use of acoustic guitars. One feels a sense of timelessness in his acoustic instruments that is very rare in any subgenre of metal. There is an effortless infusion of folk instruments and normal metal instrumentation that all but the most important black, viking, and folk metal bands struggle to emulate. Prior to this album’s release the best acoustic segments in metal were reserved for album openers, and they all had the same purpose, to lull the listener into a false sense of calm so that the force of the opening riff hits that much harder. After this album there are tons of bands that use acoustic instruments of sneaking pop hooks into their metal without losing any face. Here, however, we see neither of these extremes. The acoustics are sometimes used in introductions in the same way an 80s metal band would, but far more often they are integrated into the melody. The picking patterns he uses are gorgeous, but they never come off like he is trying to shove a pop melody into the clenched sphincter of the metal community.

The acoustic openers, far from being a means to an end, are constructed with such care in both their presentation and the integration with the heavier riffs that follow that they are able to provide an accent and overview to the character of each track. The fact that Quorthon can often reintroduce these opening riffs overtop the guitars later in the song shows how they are a foundation for his explorations rather than a cage.

The key here, I believe, lies in the effort Bathory put into producing acoustic lines that reflect the folk traditions he is drawing from. As I mentioned with the backing vocals, there is not a whole lot of evidence about what the music of antique and medieval Scandinavia sounded lie, and whatever work has been done by ethnomusicologists to reconstruct it (if any) lies outside my wheelhouse. However, despite the fact that neither Quorthon nor myself have any definite knowledge of what the music sounded like, I feel confident that his acoustic guitars have more in common with what an actual viking might play then the synthesized rebecs of many modern folk/viking bands. One of the standard pop idioms is to have a large variety of instruments playing a single melodic line so that the total harmonious effect is more far more pleasing than any of the constituent components. However, what we do know about authentic viking music is that is was typically performed by lone skalds or jesters (perhaps with some vocal accompaniment from the audience). This means that rather than relying on multiple instruments for their sound, they would have to play intricate (though static, unlike classical music) melodies complex and powerful enough for whatever instrument they held in their hands to provide all the backing music needed.

This can be confirmed by looking at the folk traditions that did survive past the advent of music notation and recording. Quorthon, however, takes these intricate folk fingerpicking patterns, and uses them as a building block for a much grander conceptual vision than the ancient traveling bards could have ever dreamed of. Future bands, with a clear path laid before them, were free to trod as recklessly as they wished, but here we see a recording of a man approaching his music like an expert gardener, carefully shaping the surroundings until all the elements fit together harmoniously.

Alright, I don’t have nearly as much to say about the bass as I do about the guitars, because it functions in a support role the majority of the time. As is often the case, it tends to stay fairly close to whatever the guitar is doing, and there are only a handful of places in the album where it really jumps out. As a side note I’ve always felt that if you play bass in a metal band at some point you made a decision to either keep out of the spotlight entirely doing the kind of work that holds the album together but does not capture much attention, or you went to the exact opposite pole and played stuff that absolutely demands the listeners attention. I know this can be attributed to cognitive bias (since the stuff that you notice stands out in your memory) but I have noticed it all the same.

“Twilight of the Gods” definitely falls into the second of those two categories, and this is not a bad thing. While the bass is hardly ever grabbing your attention (as I mentioned before, the guitars really aren’t either) it is always fulfilling a vital roles in the song, and the fairly simple riffs it plays are not a indication of any lack of prowess on Quorthon’s part, the line before the guitar solo on the title track proves that. Furthermore, he incorporates a wide variety of techniques in order to achieve this effect. On this album you can hear unison lines (where the bass plays a riff identical to the guitar), what I call semi-unison lines (where the bass either plays a riff that is almost identical to the guitar part, or plays along with the guitar for part of the riff and then branches off), steady one note per bar played on the 1 beat style minimalist playing, riffs that start out following the chord progression and then slowly expand into independent lines (or vice versa), and “plays the root of the chord but alters the rhythm between each bar” kind of playing, and sparing use of the sudden, rapid fire technically proficient bass fill.

The only major styles of playing commonly seen in metal that he does not use are the “melodically distinct but consonant with the guitar riff” approach and the “use a basic riff as a blueprint but constantly modify the melody”. Both of these, however, are the kind of thing that really draw the listener to the bass, and that is not what Quorthon is going for. Instead, Quorthon uses the bass to anchor down the guitars when they need extra force, fill some of the empty space when they are pulled back, augment the acoustics when it is necessary to do so, and in general provide the muscular system to the guitar’s flesh and blood that allows the album to progress forward.

Before I get into the drums I want to include the caveat that, unlike the guitars and bass, I have no experience actually playing them, and therefore, despite my best efforts to double check everything, there is a greater possibility of me making a mistake about the drums then the other sections. The likely place a screw up would occur is in the identification of the actual drums being used on a particular beat, as time signatures are something that is used in learning any instrument, and broader stylistic commentary is subjective. More specifically, any time there is more than one drum being played simultaneously, in addition to times when any of the numerous variety of cymbals and toms are used, there is a greater chance of error on my part. However, as luck would have it, the drums patterns on this album are are built almost entirely from the kick and snare, so it does not detract too much for me to focus on what I am more certain of. Before moving on, those that aren’t familiar with the concept of a time signature may benefit from watching a quick video on the subject or else skipping over the drum section.

The decision to have the lower end drums dominate the rhythm gives "Twilight of the Gods" a sound that is at once sparse and propulsive. I find myself reminded of the Spartans when I think about the drums on this album, in that their is an incredible sense of force present, but at the same time it is communicated in a very simplistic manner. When a delegation from the island of Samos came to Sparta with a long speech pleading for military aid against the Persian threat, the city's magistrates told them that by the time they had gotten to the end of the it, they had forgotten how it started. In response the Samians simply said "The bag needs flour." to which the Spartans informed them that including the "the bag" was unnecessary before agreeing to aid them. Similarly, on this album we see Quorthon asking about the necessity of anything but the most basic, muscular drums in metal. The decision to play in a style in which the beat is heavily emphasized gives the finished product an even greater sense of primitive power that matches very nicely with the rest of the music, lyrics, and overall theme.

This reliance on the kick and snare and focus on the beat does not imply a total absence of complexity. Throughout the album Quorthon uses a number of very intricate additive time signatures. The combined effect of this is very interesting. You always feel the album’s monumental drive, but when it is cast into a standard 4/4 mold it comes off with a sense of raw aggression, but that same power, when cast into an alternating pattern, projects the force into the realm of the mythic, as if one is witnessing a fearsome host of beings who march in a manner fitting their own transcendent nature rather than needing to conform to the steady left-right of human feet.

The lyrics of this album reward a deep understanding of Norse myth without coming off as too explanatory or obscure. While, if you are not familiar with this subject matter, you will not come away from this album with any kind of coherent picture of Odinism, even the middling knowledge I possess in the subject was rewarded with language that paints a picture of both the mythology itself as well as the psychological mindset of its practitioners. I would imagine a person with greater knowledge in this than myself would find these lyrics even more enjoyable. This is not a bad thing and far from pretentious or elitist. Someone with no understanding of Norse Myth will still be able to get some enjoyment from the way Quorthon paints scenes from earlier times, whereas if he had resorted to simply telling the Myths, then not only would more knowledgeable listeners find nothing of value in them, save perhaps a few missing gaps in their education being filled, but once these explanations had been absorbed the words would become dull and meaningless.

More importantly, the great power of this album’s lyrics come from what he sows in the mythic soil rather than the substrate itself. On the one hand you have the standard “warriors in Valhalla marching off to battle”, “hymns to the allfather”, and general mythic themes that have become standard fare in black/viking/folk metal. On the other hand, on songs like the title track and “To Enter Your Mountain”, we see Quorthon writing lyrics that take the ideals and images from Scandinavian mythology and using them as the driving force behind social and personal commentaries. Even songs like “Hammerheart”, which at first come off as your standard paean to Odin and the warriors who are found in his company, possess, like all great myths, an deep core that speaks to the human condition. In the case of the final track this manifests in the form of a admonishments not to fear the coming death that all humans must confront.

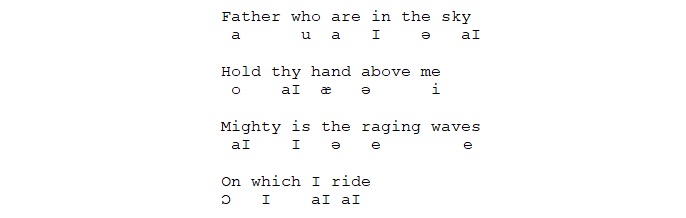

Ezra Pound, most concisely in his essay “The ABC’s of Reading”, describes poetry as being dividable into three essential qualities: melopoeia, phanopoeia, and logopoeia. Melopoeia is the basically musical quality of human words, or, “words are charged beyond their normal meaning with some musical property which further directs its meaning”. Phanopoeia is the ability of a poet to impress sensory and cognitive images on the human mind, or, “a casting of images upon the visual imagination”. Logopoeia refers to the numerous varieties of wordplay that one can engage in, or, “poetry that uses words for more than just their direct meaning, stimulating the visual imagination with phanopoeia and inducing emotional correlations with melopoeia”, or alternatively “the dance of the intellect among words”.

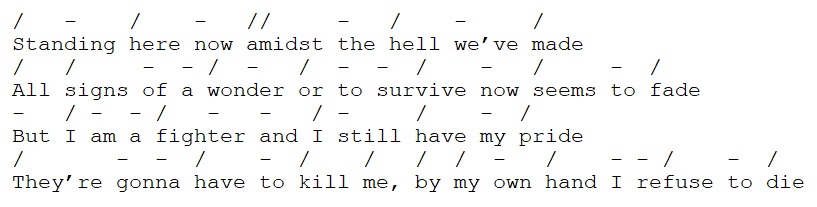

Of these three I think the melopoeia stands out the most on “Twilight of the Gods”. As in most lyrics (exempting say, a certain set forms, for instances some styles of blues standard), there is no consistent pattern a la pre-modern poetry, but this does not mean that the words are thrown about haphazardly. To illustrate this, I will take a stanza from the vocal high point of the album, “Under the Runes”, and break down the syllables. To those who have been a long time away from an English classroom, remember that / is a stressed, or long syllable and - is an unstressed, or soft one. Also keep in mind that, save in poetic forms like Iambic Pentameter where a stress pattern is deliberately heightened, the natural cadence of English does not always neatly separate between hard and soft, especially when there are gaps between the words, but this transcription is reasonably close:

The first thing to notice is that all of the crucial words (amidst, hell, wonder, survive, fighter, pride, kill, refuse, die) receive a stress mark. The second thing to notice is how, while there is no firm pattern, the middle portion of each lines receives far more stresses than the outside. Finally note that the stanza starts out with a pattern that is fairly steady and regular, then on the second line you get a few irregular beats which give the passage some extra punch (many of the stressed syllables are words that he is howling out), however, there is still an on and off pattern running through it. Then, on the third line, we see a repetition of that lovely, flowing soft, soft, hard, soft pattern that was used in the second line (”of a wonder” and ”am a fighter”) followed by more steady iambs. Finally the fourth line, the aforementioned pattern is brought back again (”gonna have to”), but this time it is in the middle of a far more hectic passage; a reflection of the protagonist’s passion that is mirrored by the intensity of Quorthon’s voice.

“Under the Runes” possesses some great phanopoeia as well, if the stanza:

“In great numbers we advance before dawn

By the great hail this great fight is born

Among the clouds now our black wings fills the air

No more frontlines the holy battle is everywhere”

doesn’t cast a vivid image in your mind, then I don’t know what will.

In terms of Logopoeia, there is none to speak of. This is fine. As Pound points out, this is the most recent addition to the poetic arsenal. You don’t see it in the Ancient Greek epics like “The Iliad”, which is a document of a fairly comparable culture to the Norse society Quorthon sings about. I don’t know enough to say with certainty, but if I had to guess one would not find any puns in the great sagas. I do know that wordplay would seem incredibly out of place in an album like this.

All in, unlike other Viking Metal this music does not come off as some elegy for times long past, but instead presents the Nordic Mythos as something present, a force with which to oppose the desolation and indulgence of the modern world.

The title track of “Twilight of the Gods” at once sets the thematic tone for the album and represents a departure from it. Save "To Enter Your Mountain", the rest of the albums lyrics deal explicitly with Odinism. Even "...Mountain" couches what is essentially a timeless subject matter in mythic terms. In contrast, the lyrics of "Twilight of the Gods" deal with the corruption of the modern world. Now those of you with some knowledge of Norse mythology may be inclined to point to the song's title and chorus as evidence of a strong Odinistic bent on this song as well, and this is where things get interesting.

For those not in the know, the twilight of the Gods is a key concept of traditional Norse religion. Better known as Ragnarök, it is a great cosmic destruction, in which the serpent Jörmungandr and the wolf Fenrir engage in an epic battle that sees all the big name deities die off and the entire planet plunge beneath the waters. I don't want to use the phrase end times because it is usually described as the climax of a recurrent cycle rather than as an eschaton, but I have heard it called both on different occasions. Regardless of the precise cosmology, for all intents and purposes the twilight of the Gods is the end of the world. All existence as we know it vanishes beneath the rising waters, save two humans and a handful of second-string Gods.

Anyone who made the connection between the Norse end times and the situation with our own polar ice caps, congratulations, you're thinking like Quorthon. In the lyrics to the title track, he uses this Norse mythological concept to rail against the corruption, short-sightedness, and decadence of the modern world. I am not going to pretend that he was the first person to figure this out. He wasn’t by a long shot. Nietzche titled his 1888 philosophical treatise "Twilight of the Idols" for the very same reason, and in it he cries out against the unrestrained excess of his own age. Since the reign of Queen Victoria we have only moved further in the direction Nietzsche warned against, giving Quorthon plenty of cause for a similar complaint. I am not going to say that Quorthon was inspired by, or even read, Nietzsche's work, because a number of people have had the same idea, and I would guess it to be even more prevalent in the land the concept came from.

In any case, regardless of where he picked it up from, his decision to open an album built around themes of Odinism with a track whose lyrics connect a key concept of the tradition with the failures of our own age (an age where the one-eyed God is conspicuously absent) was a magnificent one. By starting with an assault on modernity, he casts the rest of the album in title track's thematic light. While songs like "Under the Runes", if taken on their own, could be seen as an exploitation of the admittedly metal nature of the Norse mythos for the sake of cool sounding lyrics, this song instead places everything he describes afterwards in comparison against the world we live in. By extolling the virtue of bravery, he is also contrasting it to the cowardice of our present age. By extolling the virtues of a God that is used as an aid for a "a man [who] I hold[s] in [his] hand [his] fate", and not as a crutch, he is mocking the tendency of modern mainstream religion to cultivate blind obedience and unquestioning fervor in their followers.

The introduction, which I am going to define as the period from the start of the song to the second repetition of the backing vocals prior to the first verse kicking in, gives the listener a taste of the mastery that is on display here. I know most people would probably consider the point when the backing vocals kick in for the first time to be the transition from the intro to the main song, and I would not be surprised if, say, you went to a tablature sight and pull up the (as of November 2017 nonexistent) notation for this song, and found it marked like that. However, I am going to use this admitted unconventional demarcation because prior to the second iteration of the backing vocals, the song moves through a series of "build-ups", starting off barely audible and progressing in stages until it plateaus with the riff used for the verse.

"Twilight of the Gods" opens with silence. This empty void lingers for a while before the sound of wind, faint at first but slowly growing in intensity, enters. Next we get the slightest suggestion of the guitar riff, which in turn also builds until you are right in the middle of the intro. While I sincerely hate to say anything negative about the corpus of His Holiness St. Dio, blessed memory, it can be instructive to compare this use of wind to the opening of "Holy Diver". Before you grab the pitchforks, answer me one question. Don't think about it, just call up the first number that pops into your head. Ready. How many seconds to you have to fast forward before the actual song starts?

Most of the people reading this were probably able to get an answer in the general ballpark of the 1:20 mark (or 0:50 if they are more familiar with the version on some of his compilations). Now I can't speak for you, but I have never found myself fasting forward through the introduction of "Twilight of the Gods". That is because the entire song flows naturally out of its beginnings. You can go put on the video for "Holy Diver", and, while Dio should be rightly commended for his decision to stick to at least the spirit of, what to my unworthy ears seems like a mistake, he still needed to chop thirty seconds off of his buildup to make it even close to playable as a single. Can you imagine Quorthon being able to cut thirty seconds from "Twilight..." for any reason whatsoever? That is because the entire introduction builds up in a slow, step by step fashion to the main song. There is never a point where things "get good", but a slow but persistent march into the realm of transcendence.

Both the intro and outro remind me of the Ma-Xia school of painting found in China during the Song Dynasty. Like the affixes to "Twilight of the Gods", the Ma-Xia sought to make paintings that were dominated by empty space. From the perspective of the Western art tradition, where the way you paint a person is to have the top of their head just below the upper edge of the canvas and their feet at the bottom, this idea seems ridiculous. However, just one look at one of these paintings, such as this untitled work by Ma Yuan , and the appeal becomes immediately evident. The mind sees the handful of objects that are painted into the work, in this case a few mountain peaks, some birds, and the faintest hint of clouds, and it tries to grasp at the contents of the unadorned space. The slight suggestions of mist and fog let the imagination run wild with what majesty lies hidden behind the cloud cover. So in a similar fashion the barely audible guitars and atmospheric noise cause the ears to grasp at contextualizing what it is hearing, only to require an intervention by the imagination in order to fill in the gaps.

While it could be said that there is an actual riff in this first part, it is never explicitly introduced. Rather than playing a riff straight, vamping on it for a while, and then switching to a new riff, Quorthon approaches the opening guitar part as if he were is skilled cunnilinguist: gently skirting around the edges of his subject, coming in for just a brief moment to give a brief sense of his intentions, and then moving back around to a simple suggestion of the pattern, letting the expectation for what is to come slowly and naturally build rather than charging in head-first.

This technique is contrasted rather explicitly in the title track's second riff. It features both electric and acoustic guitars, and both are as direct, blunt, and intense in their approach as an Einsatzgruppe at a small Ukranian village (or pretty much any military force that has crossed through the Ukraine). The electric guitar pummels the same chord for bars at a time, while the acoustic guitar plays a single chord at the start of each bar in a slow-strummed, almost harp-like manner. While none of this is particularly intricate (nor is it meant to be) it is counterbalanced by the very interesting time signature Quorthon employs.

The rhythm more or less uses an additive time signature of three bars of 7/4, one bar 4/4, and then two bars of 2/4. I say more or less because the difference between four bars of 2/4, two bars of 4/4, and one bar of 8/4 is not as firm many people think. If you pay attention to the accents, I think my original notation is probably best. However, despite the fact that convention would tell you not to use 8/4 unless it is absolutely clear their is no attempt at accenting the 5 beat, given that the rhythm is in 7/4 for the previous bars and the overall sense one gets is that an extra beat is being added to the final one, in my opinion it makes sense to think of the song following a 7/4, 7/4, 7/4, 8/4 pattern , at least in terms of contemplating its structure, even if that is not the proper way of noting it.

So the basic drum pattern is an alternates between either a single kick drum on the beat, or a triplet, again with the kick drum, played during the length of a single beat. During the 7/4 bars, the triplets are played on beats 2, 6, and 7, while, using the 8/4 notation style, it they come in on the 2, 6, 7, and 8. You can see how considering it as 8/4 can be helpful for understanding, since that extra beat gives the effect of adding an extra bit of forward drive, like a free safety sprinting to make a tackle and then deciding at the last moment to deliver a running punch instead.

The contrast between the steady time and loose, free-flowing character of the first part and the rhythmically complex, firm, aggressive character of the second is absolutely wonderful. If a lesser act somehow pulled a prologue this beautiful out of their ass, when it came time to move on the listener would find himself underwhelmed by the song itself. Quorthon doesn't fuck around like that. He knows that he did something amazing out of the gate, but he also knows that letting up the momentum is for opening acts. So what does he do? Well, a couple things. First, he brings the time signature back to 4/4. This isn't a technical death metal album. He brought out that rather odd metric pattern for the overall effect it had, when paired with the rock hard guitar part, against both what came before and what came after. Before there was a delicate and intricately arranged acoustic part that varied itself on every repetition, which was contrasted against the steady pulse. The steady pulse in turn was combined with a complex meter, which, when juxtaposed against the riff of the third part, gives the listener a sense of settling into things while at the same time allowing him to boost the intensity by adding melodic and harmonic complexity.

The drums use a pattern where the kick drum plays on the first two beats, and then the snare is introduced for the second half. It follows a two bar pattern where on the first bar it plays on 3 and then on the second it plays on the 3 and 4, while the kick drum is used for the off-beats. This pattern breaks away, at least partially, from the standard way a kick and snare are used, which is to alternate them back and forth. Thus, during the end of the second bar, when we finally do get a back and forth, the effect is far more satisfying than it would be in normal circumstances. At the same time, the focus on these two drums maintains the laconic combination of force and simplicity that I described in the earlier segment on the drums.

On the guitar part, we get a two bar pattern that features two chords in the first bar, and then one chord and a little mini-riff in the second. While the guitar is playing this part, the bass is playing a line that is more or less in unison with the guitars. For the vast majority of the song the bass will perform this function, adding occasional extra notes or minor modifications to the rhythm of the guitar, but otherwise just acting as an unsung hero.

The other significant change from the second part to the third is the introduction of the backing vocals. As I mentioned earlier, I think that these secondary voice lines are one of the standout achievements in one of metal’s high water marks. People talk a lot about how the harsh vocals typically seen in black and death metal are a necessity because no other form of singing fits in with music that goes past a certain intensity threshold. This is not true. Like dropped tunings, they are a tool at the disposal of those who wish to create extreme music, they have a certain effect and that effect is an incredibly useful way for achieving a purpose. This does not mean it is the only means of doing so. Quorthon was one of the early pioneers of this style of singing on his first albums, and while the art of guttural vocals has produced innumerable varieties since those early days, the fact that many black metal bands still imitate the approach seen in the first three Bathory releases should be a clear indication that Quorthon was not one of those innovators who merely paved the way for other groups to perfect his initial forays, but one who, like Zeus, pulled a fully complete divine creation out from his head. And after having done such a magnificent job with his early vocals, Quorthon, like the protagonist of a Kung-Fu movie who returns to the very adversary who defeated him in the initial encounter with all the benefits of the training he has acquired, comes back to the question of whether clean vocals can be compellingly fit to extreme metal ready to spill blood.

I talked a bit about the backing vocals before and I will go into even more detail later on, so for now I will stick to the specific way he implements them in this track. They are pitched much higher then the deep hums seen later in the album. This fits with the overall theme of the song. It produces a sense of urgency that matches the agitated lyrics. This urgency also fits in perfectly with the rest of the vocals and instrumentation. I don't think anyone has heard those gorgeous voices come into the track and felt the sense of disparity that one often feels listening to, say, the clean vocals of an Atreyu song. These backing vocals not only fit in perfectly with the rest of the music, but they elevate the intensity of the whole (side note: there are literally no good synonyms for backing vocals).

The acoustic guitars, which had been noticeably absent during Quorthon’s spoken lyrics, are brought back during the little mini interludes that occur between stanza’s when there is no chorus present. They perform a similar function to what they did during the latter part of the introduction, playing chords in time with the electrics so that the crashing guitars come off more like the work of an ancient thunder god and less like a blitzkrieg.

During these interludes we also see the backing vocals shift up to an even higher register as Quorthon does a call and response pattern with them oddly reminiscent what you would hear between a pastor and his flock at a congregation that sings Gospel music, yet somehow not at all out of place in the rest of the music.

After one more stanza of lyrics we then get the actual chorus. I’m almost hesitant to even call it that, since the whole thing clocks in at a bit under ten seconds. However, despite that, I think that given the presence of the the lyrics during this stage of the song, and the fact that the alternation between this section and the one I describe above is the dominant pattern for this stage, the word is merited. He varies the riff and vocal pattern quite a bit during this stage. I won’t subject you to another scansion because I think it is pretty obvious that the way he sings this section is very different, however, I will give a brief treatment to the instruments.

For the longest time I thought that any riff where there is one note or power chord and then a repetition of a single note or a quick back and forth could be called a gallop riff, but in fact the term only applies to riffs that follow a pattern of either an eighth note followed by two sixteenth notes, or an eighth note followed by three sixteenth notes in triplet (so that the three of them take up the same time as two normal sixteenth notes). This means that there is not really a good term to describe the riff that Quorthon plays on both instruments, despite its prominence in metal. While he is playing an (A-B-B-B) pattern melodically, the rhythm is straight eighth notes. Still, its similar enough to a gallop that I felt it worthwhile to bring the connection up. The guitar is playing power chords while the bass echoes it with single notes, both in a high, low, low, low pattern (I really don’t feel like investing the time needed to take out my guitar and transcribe this the sake of a single paragraph of text).

The drums, meanwhile, also play in rhythm I described above, with the snare being used where the higher note/power chord is played (i.e. “A” in my earlier diagram) and the kick drum being used for the string of lower notes. This gives the whole section a sense of unity. The drums do not produce sounds clear enough for the brain classify into a singular discrete pitch, though both drums and stringed instruments have many overtones beyond just the note your brain locks in on. While your brain processes the mass of sounds that emerge from the guitar as a single note, the different tones produced by a single strike of a percussion instrument are so varied as to make precise identification by the subconscious impossible. However, you can perceive some drums as being higher than others, and the snare is definitely higher than the kick. This means that you get the sensation that the drum is mirroring the guitar in a similar manner to the bass.

A compelling reason for why I should have referred to this part as just a stage rather than a chorus is that, as soon as it is finished Quorthon returns to the regular verse pattern (with the addition of the acoustic guitar augmentation) for two bars. This is a textbook definition of how a chorus works, but then,the song returns back to the “chorus” before repeating the whole process for another loop. By calling it a chorus, I am not trying to say that this song follows a conventional pop song structure (unlike the much of the album), for this is obviously far more intricate, but I think in spirit it does what a chorus is supposed to do, i.e. acting as a sudden point of variance between verse repetitions so that things don’t get dull. I would not call the riff being played a hook a la conventional pop choruses, but I do think the sudden unity of the instruments gives the listener a sense of completeness that lines up fairly well with a traditional chorus. The biggest difference, however, between this section and a normal chorus is that the rapid oscillation between the two parts produces an effect more akin to riding in a boat over a series of waves rather than getting knocked down by a gigantic one on the shore.

In a similar vein, the instrumental section that follows the on and off section might not really qualify as a bridge, however in spirit it has a similar goal in mind. The typical desired effect of the bridge is to offer something that produces a noticeably different effect from the verse and chorus, so that when it comes in (after both aforementioned elements have already been introduced), it provides either a lull that allows the rest of the song to hit extra hard when it returns, or a place to introduce an element that is too disparate to fit with the regular verse and chorus.

What I call the bridge in “Twilight of the Gods” does not quite do either of these things. The guitar and bass riffs don’t pummel quite as hard as the chorus riff, but they are a bit more aggressive than the verse riff. The drums are also fairly similar in their pattern to the verse in particular. However, despite the fact that it is not a sudden drop or a drastic alteration, its function, to provide a change of pace between the verse and the chorus, given that the chorus itself features an alternation between a new riff and one identical to the verse. All this goes to show that Quorthon really knows what he is doing, and that he is skilled and confident enough to disassemble the traditional components of songwriting and rebuild them so that they fit his needs.

After this bridge section is complete, you then get yet another interlude where both guitars play a steady repetition of the same power chord/note, going through six different pitches before pausing on the tonic. Then the verse resumes, but this time around the backing vocals have been raised higher than they were before. The effect of this, when combined with the pause, is dramatic, which is why this technique is classic in the playbook of just about every derivative of rock or pop music.

We then go through another round of verse and chorus that are close enough to what I described above that I don’t need to go into them again, but when we get to the bridge, there is a dramatic change. Now, for the first time in the album, we see the backing vocals transition to singing actual lyrics instead of a vocalized harmony, while the lead vocals take over the wordless melodies. Before the vocal changes it felt like a fairly run of the mill transition, and then the sudden introduction of spoken words from the backing vocals produces a startling effect on the listener, which combines with the lyrics to create a sense of epic grandeur that feels very much like a climax.

However, Quorthon is not done yet, and the previous ascent was nothing but a single hill in the roller coaster. The acoustic guitars are brought back as the dominant melodic instrument, while the electrics are used to give it some extra punch at key points. Quorthon fingerpicks (I assume) a very pleasant series of argeggios, which, if taken out of the context (the thudding drums, guitar backgrounds, epic Norse lyrics) would sound like something you would hear played at a Renaissance fair. As I said repeated ad nauseam, there is a lot of guesswork involved in trying to determine what exactly the folk music of a given tradition sounds like, and because ethnomusicologists involved in both 10th century Scandinavian or 14 century English folk traditions don’t have a firm idea of what said music would sound like, one has to rely on the vague pastiche that has been embedded in the general publics mind as “traditional European folk music”. This is not necessarily a bad thing. Had Quorthon dedicated his time to perusing the Journal of the International Folk Music Council to try and develop a style of playing that reflected the true folk traditions as best as we understand them, I don’t think there is a single person reading this who has the necessary background to contextualize the music for what it is. At least he isn’t just using a dulcimer as an excuse to throw in a bunch of ill-fitting pop hooks.

While the acoustic guitar is going at it, the drums play a very gentle marching-band style pattern which ever so slightly builds in intensity as the guitars increase in frequency, until both have picked up enough momentum to come crashing into another crescendo, at which point the acoustics vanish and the song merges into a more intense interlude. Then, a dazzling bass fill that reminds me a bit of Spanish guitar playing announces the solo.

Quorthon starts out the guitar solo with a series of bends that echo the main vocal melody before suddenly slamming on the gas and driving into a style of playing that will echo the jagged intervals heard in a Slayer solo before sliding into gorgeous streams of consonance, evocations of the emotive high grandeur seen in people like the unfortunately named Jerry Fogle of Cirith Ungol, which reflect the epic power of his mythic subject, transitioning into dirgeful passages reflecting the malaise he feels at the modern world, and the searing technical proficiency aimed at by so many metal bands before morphing effortlessly into phrases someone who has been playing for a few months could get a handle on. Throughout all this the one constant is the fact that this is the work of a master craftsman who is at the height of his proficiency.

We then move onto the extended outro, which is built from the same elements, notably the slowly transitioning (before diminishing now increasing) acoustic guitars and the wind. I think the biggest thing to note here is that this is the opening track, and yet Quorthon decided to put a four minute outro on it that ends in dead silence. This is not at all typical, especially in the world of metal, where one typically uses the opener for the fastest and heaviest song on the album, saving the long complex numbers for the closing track. Quorthon, however, has never been one to let convention get in the way of building an album to his own vision, so he does not opt for that. As I said about the intro, I do not think of these extended bookends as filler. I feel they play a vital role in the overall sound. In the case of the outro, it allows everything that one has just observed to settle in, and gives the following track, “Through Blood by Thunder”, the setup it needs to slowly rise from the silence like a Phoenix.

The introduction of the second track is designed so that it could essentially be an album opener in and of itself, with its acoustic buildup and long spoken word section (note that I am lumping acoustic guitars and clean electric guitars together into this category for the purposes of this essay). This is important to note because, when taken with the title track, the overall effect is that the first song functions a self contained statement of purpose for the album, while “Through Blood by Thunder” functions as the start of the album proper. This is reflected in the lyrics as well, as we get a shift from a largely modern focus (albeit couched in instrumentals and terminology that alludes to the later lyrics) to one that looks towards the past in hopes of a solution.

Musically, this song establishes which elements introduced in the title track are going to be one-off forays and which are going to be the defining stylistic components of the album. In the later category we have the arpeggiated acoustic introduction followed by electric guitars, which are first used to punctuate key points of the rhythm and the acoustic melody, which then fluidly transform into a riff; the dominance of the kick and snare drum (though there is some use of cymbals here); the backing vocals as a means of heightening key points and sections of the song; and the use of the steady strumming of a single chord/power chord as a means of transitioning from section to section, among other things.

The two most interesting elements of this song in my opinion are the backing vocals and the guitar solo. I mentioned in the introduction that the backing vocals can be divided into two rough categories: wordless singing and lyrical singing, both of which have specific purposes. Here we see the distinction drawn fairly clearly.

When Quorthon begins to sing, we see the backing vocals come in wordlessly at the end of the second line. As Quorthon holds the final syllable of said line, Quorthons come in with a call and response style echo (remember that he does all the parts, including each backing harmony). I have occasionally encountered the idea among certain segments of the metal community that the black metal and folk metal traditions are the first subgenres of metal that have wholly extricated themselves from the influence of early American rock and roll (this idea is typically spoken by the kind of person who is extremely uncomfortable with the fact that the music they enjoy incorporates elements that were originally created by *gasp* black people). To say nothing of even the most rapid-fire blast beat’s debt to Max Roach, Fred Below, and Louie Bellson, one needs to only spend two minutes comparing recordings of black spirituals (such as this one with what Quorthon does with his backing vocals here to see how ridiculous this assertion is.

These call and response style backing vocals, like those used in the old slave chants, provide additional emphasis to every other line, thus adding variety to the verse. This is not to say that Quorthon is ripping anything off. He takes a concept that has had strong currency in rock music since the moment rock music existed and infuses it with elements that allow it to be implemented in a way that fits his am bitions, in this case imbuing them with a deep, plaintive quality via long drawn out notes that fit well with both his Norse theme and the broader disdain for modernity espoused in the title track.

The chorus of the song then shows an inversion of this approach, where the backing vocals come in and sing the main line, while solo Quorthon provides the varied responses. Since the backing vocals are the most consonant (pleasing to the ear) elements of the song, this accomplishes an effect similar to the chorus of a pop song without sacrificing any of the force or integrity of the music.

The guitar solo, like that of “Twilight of the Gods”, begins with a very simple bend-heavy melody that alludes to the main riff without aping it. It then progresses forward in cycles of intensity and relaxation like waves lapping against the shore (because I’m sure nobody is tired of me using water metaphors to describe these solos). There are a number of distinctions between great guitar solos and mediocre technical exercises, but I think some of the most important are the way the solo interacts with the underlying melody of the song itself and it’s possession of a natural sense of it’s own broader rhythm independent of the song. All good soloists respond to the chord changes of the progression with their own melodic and modifications, great soloists can always keep the melody (or riff) of the song itself in their mind and constantly incorporate, modify, vary, converge with, and distance themselves from it as they play. The greatest of soloists will treat their work as a composition in and of itself, giving it its own character while at the same time doing all of what I mentioned above. As I’m sure you’ll have no trouble guessing, I think Quorthon falls into the later category.

For a more concrete example of what I am talking about, check out this video of David Gilmour’s “Comfortably Numb” solo looped repeatedly fifteen second apart. Now, a great solo does not have to be designed so that it can be stacked in such a fashion, but the fact that said solo can indicates that Gilmour has a keen understanding of how his music relates to the repeating melody that underlies it. Now, in his case he chose to respond to that melody with a solo that is very deliberately regular in its changes, whereas Quorthon chooses to write solos that bunch up into these intense bursts and then sprawl out into gorgeous austere melodies the way a male lion will lay in wait endlessly and then suddenly spring from the brush with terrifying force, but both examples show how their respective guitarists forged their technical proficiency into something beautiful rather than squandering it on stiff scale runs or pointless flights of fancy.

With “Blood and Iron”, we really see how Quorthon takes the techniques and approaches developed in the first two songs and uses them to craft a full album. The first thing I did when writing this review was to go through each song a bunch of times and chart out the broader shape of the album. In doing so, I really came face to face with how much of this album is built around the variations in its implementations of key structural ideas. It sucks that the word formulaic has such negative connotations attached to it, and that their is no real word that describes the same concept but more positively (maybe formal, but to me that just calls up British gentry in coattails and evening gowns and not music with a strong emphasis on repeated forms). But if you think about it there is no reason for this. The restriction Quorthon imposes that almost every song features the vast majority of the devices seen here (save Hammerheart): an opening with an acoustic passage which transitions into a heavy passage built around a rhythmic chord progression, then moves on to a more riff driven electric guitar stage, perhaps preceded by a brief return of the acoustics, followed by a verse, then a chorus with greater backing vocal emphasis, and a guitar solo at the end; is far from inhibiting. The Prelude and Fugue form has a significantly greater constraint in what can and can’t be done with it, yet, even if you don’t know anything about classical music, if you encountered a person who said Bach’s “Well Tempered Clavier” was a pile of shit because all he did was write 24 Prelude and Fugues one after the other, you would know that person was an idiot.

As with Bach’s work, and the often more extreme limitations imposed on many entire subgenres of metal, these restrictions actually allow Quorthon to find greater expressive freedom than he would have otherwise. If there is not some kind of glue that holds the different songs of an album together, then it is just a collection of songs. Even the most bizarre, avant-garde, “all over the place” releases have a natural flow from song to song and certain unifying characteristics that make the album a single entity, assuming they are any good. Now these unifying elements can be firm, formal, and concrete or they can be loose and abstract, and each has their advantages, but to my mind the greatest asset in the former approach is that a skilled songwriter can really demonstrate how to express a vast spectrum of ideas over a short wavelength. Of course you have to be a gifted craftsman to really pull this off, as the more you limit yourself the harder it becomes to be inventive, and the easier it is to come off as formulaic (negative connotations intended), but at the same time assuming you are capable of succeeding, as I believe Quorthon has, the end result is all the more stunning.

The odd thing about having these kinds of patterns in place is that once the brain subconsciously recognizes them, it makes the differences between each implementation all the more striking. I don’t think the gorgeous way the backing vocals follow that gorgeous upwards-arcing melody during the bridge would be anywhere near as striking if you hadn’t been unconsciously primed to a certain pattern in the way said vocals typically function, only for your mind to be surprised when it doesn’t.

As with “Through Blood by Thunder”, I think the best way to continue my assessment of this song is to pick to standout elements and assess them in greater detail. That way I can avoid returning to the same territory too many times and I don’t end up with a novel-length writeup where I give each song as much attention as I gave the opener.

A real standout element of “Blood and Iron” is the acoustic opener, which takes place over multiple stages, which combine into a unified end result that gives the impression of a single introduction rather than a series of stages. The first part of the riff, like what we have seen prior to this, is a fingerpicked pattern that alludes to the future electric riff (albeit loosely in this at the moment). I would call what he plays a semi-arpeggio. For those who don’t know, a normal arpeggio is where you use your left hand to make chord shapes on the neck of the guitar, but then instead of playing the entire chord at once, you pluck out a pattern of individual notes, typically with the fingers and not a pick**. This is in contrast to a normal guitar riff, where the left hand will slide up and down the fretboard. Now this opening riff is not quite either of these things. It starts off with two two bar repetitions that, on the lower five strings of the guitar, feature the same position being held for the duration of each of the two phrases. On the highest string, however, Quorthon moves up and down the fretboard a bit, alternating fairly quickly between two different notes (not quickly in a speed metal since, but too quickly for it to be played as separate chord changes). This is a cousin of a well established move in the rock playbook where a strummed chord (i.e. notes played at the same time, not arpeggiated), is shifted in on the highest string (typically with a D chord to a suspended 2nd or 4th position), as can be seen in the opening riffs of Led Zeppelin’s “The Song Remains the Same” (the main riff, not that brief intro), Queen’s “Crazy Little Thing Called Love”, and many other songs in the classic rock canon. While doing it to a slower arpeggio rather than a fast chord sequence makes the end result more atmospheric and pensive rather than energetic, the intended goal is the same: to produce a greater sense of movement and vitality.

This four bar pattern is repeated a few times, and then a jagged chord is allowed to ring out alone over the silence to toll out the announcement of a new stage. This new pattern is very similar to the first, especially at the start, where there are two bar long patterns of chords being played in arpeggios with modifications to the highest note. The big difference is now each pattern is played back to back rather than going back and forth like before. After both of these patterns have been played twice, Quorthon switches to two different arpeggiated chord shapes, which he then goes on playing two times through like I previously described (for a total of eight bars, four per arpeggio pattern). These riffs, unlike the first two, do not feature any changes on the high E string. When combined with the extended duration of the passage, the sense of movement I described in the paragraph above begins to perceptibly still.

All of this solidifying, however, is just in preparation for the final stage, which is by far the most fluid. Unlike the previous patterns, which were arpeggios with slight modifications, Quorthon now introduces a fuller gambit of techniques to the riff. The dominant element is still the individual plucked chord notes, but they are now interspersed with strummed chords and hammer-ons, creating a vibrant sound. This is enhanced by the sense of rhythm, which, like the solos I described before, features an oscillating sense of intensity. Things will come to a complete halt and then shoot forward rapidly, again coming off like something with its own sense of propulsion rather than being enslaved to the metronome. Oddly enough, despite the more erratic nature of this riff, it at the same time provides a much closer outline to the shape of the electric riff that proceeds it, thus when it finally does come on, the steady, heavy chords give one the sense that the loose acoustic patterns are being hammered in place.

The other important element I wanted to talk about is the lyrics. I mentioned Ezra Pound’s three-fold classification system of poetry, which I think is as good a metric as any, where poetry can be grouped into melopoeia (essentially the musical quality of human language), phanopoeia (essentially the ability to produce an sense image in the imagination), and logopoeia (essentially wordplay). There is no logopoeia on this album, and that is fine, if not preferable, since this was the latest addition to the poetic arsenal, and is not seen in early poets like Homer, nor, would I guess, in the Norse skjalds. The melopoeia on this album is, as I said before, impressive, especially for someone whose native language is not English, as it is very difficult for for a non-native speaker of a language, even one who is as obviously fluent as Quorthon was, to grasp the subtle nuances of its natural rhythm, flow, and meter. However, at least as far as “Blood and Iron” goes, the phanopoeia is the standout element. Consider the following lines:

“The story tells of raging winds

Black clouds gathered up high

And of lightning striking from a

Burning bloodred sky

The mountains crumbled to the seas

Earth shook the worlds collide

Ending the age of gods

Giving birth to our time”

If reading those lines does not produce a firm image in your mind, like the sun’s light suddenly vanishing as ominous clouds cast a veil of darkness over you, only for your sight to be restored not by the source of this planet’s life, but by impossibly massive fires igniting a conflagration of the blackness above you, then as you turn to see where you can run for cover, all you can glimpse from the illumination of the glimmering flames as the surrounding landscapes that you thought were eternal crumble to ashes; well there really isn’t anything I can say to help you.

“Under the Runes”, is, in my opinion, side by side with the opener as the standout song of this album. This evocation of ancient warfare pushes the tensile strength of the aforementioned form I have described to its absolute limits. This is a fitting place for such an endeavor. The act of warfare is the most extreme circumstance a human being can find themselves in. While the modern world with its hidden snipers and constant danger of surprise IEDs has filtered out any of the old sense of valor, for most of human history it has been the greatest paradox: an event of unequaled suffering that somehow casts an unbreakable spell on mankind so that, despite knowing that even in the best of circumstances, the pains outweigh the pleasures, we still find ourselves drawn towards it again and again.

Quorthon, like Homer in The Illiad, refuses to shy away from either the enchanting power or the total misery of warfare. Just as the greatest poet (save Dante) demonstrates no difficulty showing this paradox in scenes such as when Patroclus, in a fit of battlefield ecstasy, charges down Thestor, a Trojan charioteer “crazed by fear.. Ramming the spearhead square between his teeth so hard he hooked him by that spearhead over the chariot rail, hoisted, dragged the Trojan as an angler perched on a jutting rock ledge drags some fish from the sea” (Fagles 16.478-89), Quorthon refuses to hide from our ears either the siren call of battle or the horrific fate of those who hear it, singing of going to the house of death with a “great hail” in one line, and then acknowledging that he is in the middle of a “hell” where any chance to “survive now seems to fade”.

The dominant vehicle Quorthon uses to showcase this polarity is his the vocal performance. All of the elements I have described in previous songs are firing on all cylinders: the acoustic opener is the most evocative and intricate in the album, jumping right into a full force hybrid of arpeggios, strums, and hammer-ons similar to what was employed in the final stages of “Blood and Iron”s introduction; the main guitar riff is the most emotionally-imbued in the album, employing the closest thing to a legit hook we will see at the exact point when the music needs the most significant response from the listener; the kick drums pound out a beat that feels like the steady rhythm of feet at the start of the song, and progresses into a frenzied assault on the kit that showcases what can be done with an emphasis on the two most fundamental drums. However, it is through Quorthon’s voice that the joy of Patroclus and the torments Thestor are brought to life.